Atlantic Salmon

Facts

Also known as: Bay Salmon, Black Salmon, Caplin-cull Salmon, Fiddler, Grilse, Grilt, Kelt, Landlocked Salmon, Ouananiche, Outside Salmon, Parr, Sebago Salmon, Silver Salmon, Slink, Smolt, Spring Salmon, Winnish.

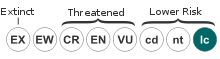

Conservation Status: Least Concern

Location: Atlantic Ocean

Lifespan:

Also known as: Bay Salmon, Black Salmon, Caplin-cull Salmon, Fiddler, Grilse, Grilt, Kelt, Landlocked Salmon, Ouananiche, Outside Salmon, Parr, Sebago Salmon, Silver Salmon, Slink, Smolt, Spring Salmon, Winnish.

Conservation Status: Least Concern

Location: Atlantic Ocean

Lifespan:

Scientific Classification

Kingdom: Animalia

Phylum: Chordata

Class: Actinopterygii

Order: Salmoniformes

Genus: Salmo

Species: S. Salar

Binomial name: Salmo Salar

Kingdom: Animalia

Phylum: Chordata

Class: Actinopterygii

Order: Salmoniformes

Genus: Salmo

Species: S. Salar

Binomial name: Salmo Salar

Description

The colouration of young Atlantic salmon does not resemble their adult stage. While they live in freshwater, they have blue and red spots. While they mature, they take on a silver blue sheen. When adult, the easiest way of identifying them is by the black spots predominantly above the lateral line, although the caudal fin is usually unspotted. When they reproduce, males take on a slight green or red colouration. The salmon has a fusiform body, and well developed teeth. All fins, save the adipose, are bordered with black.

The colouration of young Atlantic salmon does not resemble their adult stage. While they live in freshwater, they have blue and red spots. While they mature, they take on a silver blue sheen. When adult, the easiest way of identifying them is by the black spots predominantly above the lateral line, although the caudal fin is usually unspotted. When they reproduce, males take on a slight green or red colouration. The salmon has a fusiform body, and well developed teeth. All fins, save the adipose, are bordered with black.

Behaviour

Fry and parr have been said to be territorial, but evidence showing that they guard territories is inconclusive. While they may occasionally be aggressive towards each other, the social hierarchy is still unclear. Many have been found to school, especially when leaving the estuary.

Adult Atlantic salmon are considered much more aggressive than other salmon and are more likely to attack other fish than others. Where they have become an invasive threat it has become a concern that they are attacking native salmon such as Chinook salmon and Coho salmon.

Fry and parr have been said to be territorial, but evidence showing that they guard territories is inconclusive. While they may occasionally be aggressive towards each other, the social hierarchy is still unclear. Many have been found to school, especially when leaving the estuary.

Adult Atlantic salmon are considered much more aggressive than other salmon and are more likely to attack other fish than others. Where they have become an invasive threat it has become a concern that they are attacking native salmon such as Chinook salmon and Coho salmon.

Predators or Prey?

The Atlantic Salmon's predators are Seals, birds, and most larger fish. Predators also consist of humans for hunting/fishing. Over-fishing is a great problem for the Atlantic Salmon. The Atlantic Salmon's prey are invertebrates, terrestrial insects, amphipods, euphausiids, gammarids, and smaller fishes,

The Atlantic Salmon's predators are Seals, birds, and most larger fish. Predators also consist of humans for hunting/fishing. Over-fishing is a great problem for the Atlantic Salmon. The Atlantic Salmon's prey are invertebrates, terrestrial insects, amphipods, euphausiids, gammarids, and smaller fishes,

Diet

Young salmon begin a feeding response within a few days. After the yolk sac is absorbed by the body, they begin to hunt. Juveniles start with tiny invertebrates, but as they mature, they may occasionally eat small fish. During this time, they hunt both in the substrate and in the current. Some have been known to eat salmon eggs. The most commonly eaten foods include caddisflies, blackflies, mayflies, and stoneflies.

As adults, the fish feed on much larger food: Arctic squid, sand eels, amphipods, Arctic shrimp, and sometimes herring, and the fishes' size increases dramatically.

Young salmon begin a feeding response within a few days. After the yolk sac is absorbed by the body, they begin to hunt. Juveniles start with tiny invertebrates, but as they mature, they may occasionally eat small fish. During this time, they hunt both in the substrate and in the current. Some have been known to eat salmon eggs. The most commonly eaten foods include caddisflies, blackflies, mayflies, and stoneflies.

As adults, the fish feed on much larger food: Arctic squid, sand eels, amphipods, Arctic shrimp, and sometimes herring, and the fishes' size increases dramatically.

Habitat

Atlantic salmon do not require salt water, however, and numerous examples of fully freshwater ("landlocked") populations of the species exist throughout the Northern Hemisphere. In North America, the landlocked strains are frequently known as ouananiche.

Atlantic salmon do not require salt water, however, and numerous examples of fully freshwater ("landlocked") populations of the species exist throughout the Northern Hemisphere. In North America, the landlocked strains are frequently known as ouananiche.

Conservation

Beginning around 1990 the rates of Atlantic salmon mortality at sea more than doubled, and by 2000 the numbers of Atlantic salmon had dropped to critically low levels. In the western Atlantic fewer than 100,000 of the important multi-sea-winter salmon were returning. Rivers of the coast of Maine, plus southern New Brunswick and much of mainland Nova Scotia saw runs drop precipitously, and even disappear.

Beginning in the mid-1990s the Atlantic Salmon Federation in cooperation with partners were developing sonic tracking technology, and by 2008 the salmon have been tracked from rivers such as the Restigouche and the Miramichi as far along their migration routes as the Strait of Belle Isle, between Labrador and Newfoundland - and half way to feeding grounds in Greenland.

For whatever reasons, possibly related to improvements in ocean feeding grounds, returns in 2008 have been very positive. On the Penobscot returns had been about 940 in 2007, and by mid-July 2008 the return was 1,938. Similar stories were played out in rivers from Newfoundland to Quebec.

The problems at sea remain, and there is a concerted international effort called SALSEA, to find out more about the mortality at sea. It is organized by the North Atlantic Salmon Conservation Organization (NASCO).

Around the North Atlantic, efforts to restore salmon to their native habitats are underway and there is some slow but steady progress. Restoration and protection of the habitat itself is key to this process but issues of excessive harvest and competition with farmed and escaped salmon are also primary considerations. In the Great Lakes, Atlantic salmon have been introduced successfully, but the actual percentage of salmon reproducing naturally is very low. Most are stocked annually. Atlantic salmon were native to Lake Ontario but were extirpated by habitat loss and overfishing in the late 19th century. The state of New York has since been annually stocking its adjoining rivers and tributaries with the fish and in many cases does not allow active pursuit of the species. Wild salmon on entering rivers as adults have characteristically pointed fins which help scientists distinguish from farmed or escaped salmon.

Beginning around 1990 the rates of Atlantic salmon mortality at sea more than doubled, and by 2000 the numbers of Atlantic salmon had dropped to critically low levels. In the western Atlantic fewer than 100,000 of the important multi-sea-winter salmon were returning. Rivers of the coast of Maine, plus southern New Brunswick and much of mainland Nova Scotia saw runs drop precipitously, and even disappear.

Beginning in the mid-1990s the Atlantic Salmon Federation in cooperation with partners were developing sonic tracking technology, and by 2008 the salmon have been tracked from rivers such as the Restigouche and the Miramichi as far along their migration routes as the Strait of Belle Isle, between Labrador and Newfoundland - and half way to feeding grounds in Greenland.

For whatever reasons, possibly related to improvements in ocean feeding grounds, returns in 2008 have been very positive. On the Penobscot returns had been about 940 in 2007, and by mid-July 2008 the return was 1,938. Similar stories were played out in rivers from Newfoundland to Quebec.

The problems at sea remain, and there is a concerted international effort called SALSEA, to find out more about the mortality at sea. It is organized by the North Atlantic Salmon Conservation Organization (NASCO).

Around the North Atlantic, efforts to restore salmon to their native habitats are underway and there is some slow but steady progress. Restoration and protection of the habitat itself is key to this process but issues of excessive harvest and competition with farmed and escaped salmon are also primary considerations. In the Great Lakes, Atlantic salmon have been introduced successfully, but the actual percentage of salmon reproducing naturally is very low. Most are stocked annually. Atlantic salmon were native to Lake Ontario but were extirpated by habitat loss and overfishing in the late 19th century. The state of New York has since been annually stocking its adjoining rivers and tributaries with the fish and in many cases does not allow active pursuit of the species. Wild salmon on entering rivers as adults have characteristically pointed fins which help scientists distinguish from farmed or escaped salmon.

Reproduction

The species constructs a nest or "redd" in the gravel bed of a stream. The female creates a powerful downdraught of water with her tail near the gravel to excavate a depression. After she and a male fish have respectively shed eggs and milt (sperm) upstream of the depression, the female again uses her tail, this time to shift gravel to cover the eggs and milt which have lodged in the depression. At sea, the species is found mainly in the waters off Greenland and in migrations to and from its natal streams.

The species constructs a nest or "redd" in the gravel bed of a stream. The female creates a powerful downdraught of water with her tail near the gravel to excavate a depression. After she and a male fish have respectively shed eggs and milt (sperm) upstream of the depression, the female again uses her tail, this time to shift gravel to cover the eggs and milt which have lodged in the depression. At sea, the species is found mainly in the waters off Greenland and in migrations to and from its natal streams.