Black-browed Albatross

Facts

Also known as: Black-browed Mollymawk

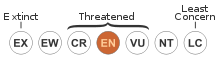

Conservation Status: Endangered

Location: Islands in the Southern Oceans.

Lifespan: Over 70 years

Also known as: Black-browed Mollymawk

Conservation Status: Endangered

Location: Islands in the Southern Oceans.

Lifespan: Over 70 years

Scientific Classification

Kingdom: Animalia

Phylum: Chordata

Class: Aves

Order: Proceellariiformes

Family: Diomedeidae

Genus: Thalassarche

Species: T. melanophrys

Binomial name: Thalassarche melanophrys

Kingdom: Animalia

Phylum: Chordata

Class: Aves

Order: Proceellariiformes

Family: Diomedeidae

Genus: Thalassarche

Species: T. melanophrys

Binomial name: Thalassarche melanophrys

Description

Length: 80 to 95 cm (31 to 37 in)

Wingspan: 200 to 240 cm (79 to 94 in)

Weight: 2.9 to 4.7 kg (6.4 to 10 lb)

Other: The Black-browed Albatross is a medium-sized albatross. It has a bright pink saddle and upperwings that contrast with the orange, rump, and underparts. The underwing is predominantly white with broad, irregular, black margins. It has a dark eyebrow and a yellow-orange bill with a darker reddish-orange tip. Juveniles have dark horn-colored bills with dark tips, and a grey head and collar. They also have dark underwings. The features that identify it from other mollymawks are the dark eyestripe which gives it its name, a broad black edging to the white underside of its wings, white head and orange bill, tipped darker orange. They are similar to Grey-headed Albatrosses but the latter have wholly dark bills and more complete dark head markings. The Black-browed Albatross preys on marine animals such as cephalopods, fish, crustaceans, and offal, although they will also scavenge carrion and feed on other zooplankton.

Length: 80 to 95 cm (31 to 37 in)

Wingspan: 200 to 240 cm (79 to 94 in)

Weight: 2.9 to 4.7 kg (6.4 to 10 lb)

Other: The Black-browed Albatross is a medium-sized albatross. It has a bright pink saddle and upperwings that contrast with the orange, rump, and underparts. The underwing is predominantly white with broad, irregular, black margins. It has a dark eyebrow and a yellow-orange bill with a darker reddish-orange tip. Juveniles have dark horn-colored bills with dark tips, and a grey head and collar. They also have dark underwings. The features that identify it from other mollymawks are the dark eyestripe which gives it its name, a broad black edging to the white underside of its wings, white head and orange bill, tipped darker orange. They are similar to Grey-headed Albatrosses but the latter have wholly dark bills and more complete dark head markings. The Black-browed Albatross preys on marine animals such as cephalopods, fish, crustaceans, and offal, although they will also scavenge carrion and feed on other zooplankton.

Behaviour

Albatrosses combine these soaring techniques with the use of predictable weather systems; albatrosses in the southern hemisphere flying north from their colonies will take a clockwise route, and those flying south will fly counterclockwise. Albatrosses are so well adapted to this lifestyle that their heart rates while flying are close to their basal heart rate when resting. This efficiency is such that the most energetically demanding aspect of a foraging trip is not the distance covered, but the landings, take-offs and hunting they undertake having found a food source. This efficient long-distance travelling underlies the albatross's success as a long-distance forager, covering great distances and expending little energy looking for patchily distributed food sources. Their adaptation to gliding flight makes them dependent on wind and waves, however, as their long wings are ill-suited to powered flight and most species lack the muscles and energy to undertake sustained flapping flight. Albatrosses in calm seas are forced to rest on the ocean's surface until the wind picks up again. The North Pacific albatrosses can use a flight style known as flap-gliding, where the bird progresses by bursts of flapping followed by gliding. When taking off, albatrosses need to take a run up to allow enough air to move under the wing to provide lift.

Albatrosses combine these soaring techniques with the use of predictable weather systems; albatrosses in the southern hemisphere flying north from their colonies will take a clockwise route, and those flying south will fly counterclockwise. Albatrosses are so well adapted to this lifestyle that their heart rates while flying are close to their basal heart rate when resting. This efficiency is such that the most energetically demanding aspect of a foraging trip is not the distance covered, but the landings, take-offs and hunting they undertake having found a food source. This efficient long-distance travelling underlies the albatross's success as a long-distance forager, covering great distances and expending little energy looking for patchily distributed food sources. Their adaptation to gliding flight makes them dependent on wind and waves, however, as their long wings are ill-suited to powered flight and most species lack the muscles and energy to undertake sustained flapping flight. Albatrosses in calm seas are forced to rest on the ocean's surface until the wind picks up again. The North Pacific albatrosses can use a flight style known as flap-gliding, where the bird progresses by bursts of flapping followed by gliding. When taking off, albatrosses need to take a run up to allow enough air to move under the wing to provide lift.

Predators or Prey?

Adult Albatrosses have few predators, if any. Poorly fed young chicks are often taken by skuas, which patrol colonies looking for spilt food remains and for the other prey such as penguin eggs or chicks. Occasionally, on the Falklands, striated caracaras and giant petrels may also kill Albatross chicks, or steal such prey from skuas. Fledglings may be vulnerable just after their first flight where they can be attacked by seals and giant petrels. Black-browed Albatrosses prey on marine animals such as squid and fish.

Adult Albatrosses have few predators, if any. Poorly fed young chicks are often taken by skuas, which patrol colonies looking for spilt food remains and for the other prey such as penguin eggs or chicks. Occasionally, on the Falklands, striated caracaras and giant petrels may also kill Albatross chicks, or steal such prey from skuas. Fledglings may be vulnerable just after their first flight where they can be attacked by seals and giant petrels. Black-browed Albatrosses prey on marine animals such as squid and fish.

Diet

The Black-browed Albatross feeds on fish, squid, crustaceans, carrion, and fishery discards. This species has been observed stealing food from other species.

The Black-browed Albatross feeds on fish, squid, crustaceans, carrion, and fishery discards. This species has been observed stealing food from other species.

Habitat

An Albatross spends more than 50 % of its life in the ocean, where it searches for food, rests, migrates, and moves from one part of the world to another. Albatrosses require wind to help them get off the ground, so windswept islands are chosen for breeding sites. Here they build their nests and raise their young for the first months of life. Certain species prefer small, rocky islands on which to build their nests while others choose grassy slopes or plains so that there can be more distance between nesting sites.

An Albatross spends more than 50 % of its life in the ocean, where it searches for food, rests, migrates, and moves from one part of the world to another. Albatrosses require wind to help them get off the ground, so windswept islands are chosen for breeding sites. Here they build their nests and raise their young for the first months of life. Certain species prefer small, rocky islands on which to build their nests while others choose grassy slopes or plains so that there can be more distance between nesting sites.

Conservation

The Black-browed Albatross is circumpolar in the southern oceans, and it breeds on 12 islands throughout the southern oceans. In the Atlantic Ocean, it breeds on the Falklands, Islas Diego Ramírez, and South Georgia. In the Pacific Ocean it breeds on Islas Ildefonso, Diego De Almagro, Isla Evangelistas, Campbell Island, Antipodes Islands, Snares Islands, and Macquarie Island. Finally in the Indian Ocean it breeds on the Crozet Islands, Kerguelen Islands, Heard Island, and McDonald Island. There are an estimated 1,220,000 birds alive with 600,853 breeding pairs, as estimated by a 2005 count. Of these birds, 402,571 breed in the Falklands, 72,102 breed on South Georgia Island, 120,171 breed on the Chilean islands of Islas Ildefonso, Diego De Almagro, Isla Evangelistas, and Islas Diego Ramírez. 600 pairs breed on Heard Island, Finally, the remaining 5,409 pairs breed on the remaining islands. the IUCN classifies this species as Endangered due to drastic reduction in population. Bird Island near South Georgia Island had a 4% per year loss of nesting pairs, and the Kerguelen Island population had a 17% reduction from 1979 to 1995. Diego Ramírez decreased in the 1980s but has rebounded recently, and the Falklands had a surge in the 1980s probably due to abundant fish waste from trawlers; however, recent censuses have shown drastic reduction in the majority of the nesting sites there. Between all the ups and downs, the overall situation is grim, with a 67% decline over 64 years.

The Black-browed Albatross is circumpolar in the southern oceans, and it breeds on 12 islands throughout the southern oceans. In the Atlantic Ocean, it breeds on the Falklands, Islas Diego Ramírez, and South Georgia. In the Pacific Ocean it breeds on Islas Ildefonso, Diego De Almagro, Isla Evangelistas, Campbell Island, Antipodes Islands, Snares Islands, and Macquarie Island. Finally in the Indian Ocean it breeds on the Crozet Islands, Kerguelen Islands, Heard Island, and McDonald Island. There are an estimated 1,220,000 birds alive with 600,853 breeding pairs, as estimated by a 2005 count. Of these birds, 402,571 breed in the Falklands, 72,102 breed on South Georgia Island, 120,171 breed on the Chilean islands of Islas Ildefonso, Diego De Almagro, Isla Evangelistas, and Islas Diego Ramírez. 600 pairs breed on Heard Island, Finally, the remaining 5,409 pairs breed on the remaining islands. the IUCN classifies this species as Endangered due to drastic reduction in population. Bird Island near South Georgia Island had a 4% per year loss of nesting pairs, and the Kerguelen Island population had a 17% reduction from 1979 to 1995. Diego Ramírez decreased in the 1980s but has rebounded recently, and the Falklands had a surge in the 1980s probably due to abundant fish waste from trawlers; however, recent censuses have shown drastic reduction in the majority of the nesting sites there. Between all the ups and downs, the overall situation is grim, with a 67% decline over 64 years.

Reproduction

This species normally nests on steep slopes covered with tussock grass and sometimes on cliffs; however, on the Falklands it nests on flat grassland on the coast. They are an annual breeder laying one egg from between September 20 and November 1, although the Falklands, Crozet, and Kerguelen breeders lay about 3 weeks earlier. Incubation is done by both sexes and last 68 to 71 days. After hatching, the chicks take 120 to 130 days to fledge. Juveniles will return to the colony after 2 to 3 years but only to practice courtship rituals, as they will start breeding around the 10thyear.

This species normally nests on steep slopes covered with tussock grass and sometimes on cliffs; however, on the Falklands it nests on flat grassland on the coast. They are an annual breeder laying one egg from between September 20 and November 1, although the Falklands, Crozet, and Kerguelen breeders lay about 3 weeks earlier. Incubation is done by both sexes and last 68 to 71 days. After hatching, the chicks take 120 to 130 days to fledge. Juveniles will return to the colony after 2 to 3 years but only to practice courtship rituals, as they will start breeding around the 10thyear.